VENUS, Pa. (EYT/D9) — Gwen Siegel sat in the doctor’s office at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

She listened to the words. They didn’t completely register.

“You can never play sports again,” the doctor said.

To Siegel, just an eighth-grader in the North Clarion County School District at the time, that sentence was unacceptable. Basketball was a big part of her life, even though she had yet to flourish on the court.

A birth defect saw to that — the same reason she was getting this sobering news.

Siegel was born with pectus excavatum. It’s a connective tissue defect, more common in boys than in girls, that causes the sternum to grow inward. Cases can range from mild to severe.

Siegel’s case was severe.

Her chest was caved it. Her ribs flared outward. As she got older, the condition only worsened.

It affected her lungs and her heart. The bottom of her breastbone was just a centimeter from her spine.

By the time the recent North Clarion graduate was 6, she was already seeing doctors to determine what to do. When she was 13, there was no more debate.

It was time for reconstructive surgery.

“My lungs only filled to 50%,” Siegel said. “My heart was on the opposite side of my chest.

“It started affecting the way I played in seventh and eighth grade,” she added. “I couldn’t play for more than maybe five minutes at a time. I would run out of breath so quickly. It was my normal. I just lived with it.”

What Siegel couldn’t live with, though, was that diagnosis from the doctor at Children’s.

She was not willing to give up sports — namely basketball.

“I wasn’t really that good,” Siegel said. “But sports, basketball, was my life.”

What was most maddening to Siegel was the manner in which the news was delivered.

“It was super crazy because I had been going to Children’s since I was a child and they had never mentioned that I wouldn’t be able to play sports until a year leading up to the surgery,” Siegel said. “They just mentioned it so nonchalantly, and I was like, ‘This isn’t something I want.’ I even refused to get the surgery. My parents, though, were like, ‘This is a health risk at this point.’”

So Siegel and her family sought a second opinion at the Cleveland Clinic.

The first thing Siegel asked was if she could play sports.

“Sure,” the doctor said. “Why wouldn’t you?”

With that settled, Siegel prepared for the surgery. It wouldn’t come until the end of her freshman year at North Clarion.

Siegel played on the junior varsity basketball team that year for the Wolves. She admits she didn’t play very well.

“I couldn’t breathe,” she said. “My freshman year was kind of just a dud. I was just kind of there. I kind of was just on the team.”

Siegel finally had surgery on May 30, 2019.

The repair of the defect was extensive. Her Cleveland Clinic doctor, a heart specialist who also did chest reconstruction, told her it was the second worst case of pectus excavatum he had ever seen in 30 years of practicing medicine.

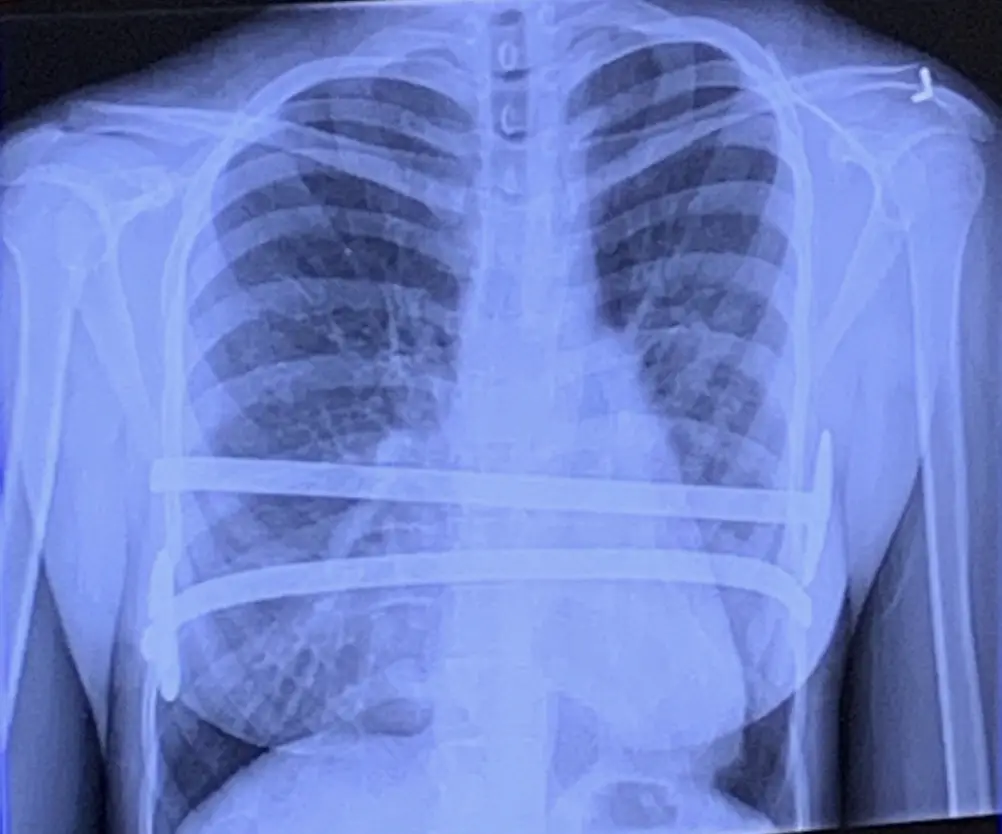

(Gwen Siegel’s chest x-ray after her surgery shows the two 14-inch titanium bars used to stabilize her sternum.)

Surgeons separated her sternum from her ribcage and pinned it back in the proper place. Two 14-inch titanium bars were also implanted across her chest to stabilize her breastbone.

The surgery took nearly four hours.

But it was a success.

“When I woke up from surgery,” Siegel said, “I remember my chest being completely normal. Flat.”

The recovery was long.

Siegel spent five days in the hospital. She couldn’t stand for weeks. Walk for a month. She had to sleep sitting upright for three to four months.

And the pain was excruciating.

“I will never wish that pain on anybody, no matter how much I do not like them,” Siegel said, chuckling. “I would never want anybody to go through that.

“People don’t realize how much weight you carry on your chest when you’re standing up until you actually go through something like that,” Siegel added. “Standing up and walking on my own was super difficult for me because of how much pain I was in.”

Once healed, Siegel felt the difference immediately.

She could breathe again. Her heart was no longer squeezed. She began to excel on the basketball court.

“The first time I played it was like, ‘Oh my God. This is amazing,’” Siegel said. “It’s crazy I lived like that all my life.”

Siegel also felt better about herself.

Before the surgery, she was extremely self-conscious about her appearance.

“I would refuse to wear anything that would show off my chest,” Siegel said. “I would wear high-neck shirts. I wouldn’t wear swimsuits, basically anything that went below my collarbone. I was super, super insecure about it. After, it was just awesome. I felt so much more confident with myself.”

Siegel has 11 scars. Some are small. Two are longer than the rest — four inches on either side of her lower chest.

When she finally returned to the basketball court, she had to overcome something a bit unexpected.

Fear.

Siegel said she could sometimes feel those two 14-inch titanium bars move inside her chest, especially when she took contact — and she took a lot of it as a 5-foot-11 center who did most of her damage in the paint. Physical play, after all, goes with the territory under the glass.

“Getting pushed around the basketball court was super scary,” Siegel said. “It even was, sometimes, during my senior year. Those bars move because they are connected to my ribs, so if I take a shot to the ribs in a certain way, my bars will shift.”

It was a strange sensation when they did. Unsettling even.

Especially in her first real action after the surgery.

“It felt so weird. It was hard,” Siegel said. “My sophomore year, I actually wore padding underneath my uniform because I was so scared. I remember the first time I played. We were at Gannon University for a team thing before the season started, and I remember getting knocked to the floor and I felt my bars move. I thought they were going to get knocked out or fall out. I just started crying so hard and made coach take me out.”

(Siegel wore padding under her uniform during her sophomore year to protect her surgically repaired breastbone.)

Over time, however, Siegel adjusted to that peculiar feeling. The more she played, the more at ease she became with her surgically repaired breastbone.

She certainly wasn’t shy about mixing it up inside. Siegel’s post moves and fearlessness is what made her a standout player for the Wolves.

It took time, however.

Siegel averaged 4.1 points per game during her sophomore season, but she showed flashes of the player she would become.

She averaged 11 points per game as a junior and was a star for North Clarion as a senior, putting up 12.9 points and 8.1 rebounds per contest.

Siegel’s corrected sternum defect was only a part of the reason for her basketball breakout.

North Clarion coach Terry Dreihaup also deserves credit, she said.

“I was just playing so well because I could breathe,” Siegel said. “That’s really when I felt like I excelled. Then (Dreihaup) asked if I ever thought about playing in college. That’s when I really was like, ‘Wow. This is surreal. I can play in college.’ And from there I just worked and worked at it. He pushed me in ways I don’t think anybody else could considering my circumstances.”

This summer, she finally achieved her longtime dream. Siegel signed to play college basketball at Penn State Behrend.

It’s always special when a high school athlete gets a chance to play at the next level. For Siegel, though, it was even more meaningful.

“I’m so excited,” Siegel said. “I really don’t know what to say.”

She is completely cleared now. The two titanium bars were removed recently and her sternum is 100% healed — and right where it is supposed to be.

“Now I’m just gonna live a normal life,” Siegel said. “Just like any other person.”

The experience did alter the way she thinks about things. She’s grateful for every opportunity she is given.

“It does make me appreciate it,” Siegel said. “To be able to play at the college level, it’s just a dream come true. It’s just a surreal feeling.”